The Tate Britain restaurant mural saga is a compelling case research of the dilemmas of the up to date museum. The racist imagery in Rex Whistler’s The Expedition in Pursuit of Uncommon Meats (1926-27), had till 2013 gone unacknowledged—formally, at the very least. Restored in that yr, the mural was then accompanied by a booklet acknowledging the content material. An indication appeared a number of years later on the restaurant entrance. Nevertheless it appears most diners ignored the imagery, as they’d since its creation.

I’ve to confess my very own complicity: earlier than turning into a author in 2005, as a Tate press officer, I lunched sometimes in that restaurant. The chained Black little one and his bare mom in a close-by tree in Whistler’s design should not hidden however slap bang in the course of one aspect of the mural. Nonetheless, I don’t keep in mind seeing them, which now appears inexplicable. Like so many others, I solely grew to become conscious of the complete horror of Whistler’s portray when the critic duo The White Pube drew consideration to it in 2020.

In distinction to Chris Ofili’s flawed work responding to the 2017 Grenfell catastrophe over Tate Britain’s staircase—the issues with the commissioning and content material of which the artist and author Morgan Quaintance addressed (amongst a lot else) in Artwork Month-to-month’s March problem—the gallery has acquired the response to the mural furore proper.

Crucially, it first invited figures from outdoors the organisation to debate what must be carried out. They included artists and artwork historians, in addition to teachers and younger folks. One of many group’s chairs, Amia Srinivasan, an Oxford professor of social and political principle, articulated key questions: “Might the area be utilized by artists of color as a inventive website of re-appropriation? Or would this unfairly burden them with an issue produced by a traditionally white establishment?”

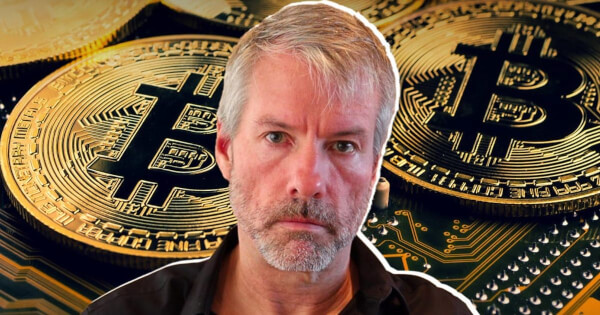

For Keith Piper, a veteran of the BLK Artwork Group in Eighties Britain, it has proved removed from a burden. Piper—whose 2007 Misplaced Vitrines challenge had provided a robust response to the Georgian and Regency rooms of the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the hidden tales of slavery and colonial oppression of their midst—has all the time grounded his work in analysis. And Viva Voce, his two-channel video set up made in response to the Whistler mural, dives deep into the archives to tell an unflinching have a look at the mural, its creation and motivations.

It takes Whistler’s youth when he made the work as a springboard for a dialog—therefore “viva”—between the flippant artist, performed by Ian Pink, and a tutorial, Professor Shepherd, carried out by Ellen O’Grady. In addition to asking him to elucidate his intentions and his use of images, Professor Shepherd highlights different Whistler works that time to his overt racism. She refers back to the textual content concocted by Whistler together with his pal, the author Edith Olivier, unseen at first, however printed by the Tate in 1954—itself laden with racist language.

Keith Piper, Viva Voce (2024) Picture: Movie nonetheless © Keith Piper

Importantly, Piper, by way of the professor, would not enable Whistler, Olivier, Tate et al the drained and acquainted get-out clause that these have been frequent views in that interval and we shouldn’t be judging them by up to date values and moralities. No: because the movie explains, amongst different issues, Whistler and the opposite Vibrant Younger Issues in his circle had ample alternative to expertise Black excellence in Nineteen Twenties London, not least within the performances of the cabaret singer Florence Mills and jazz musicians.

Viva Voce is precisely the sort of “subversive transformation” that Robert Bevan requires in his ebook about contested heritage, Monumental Lies: a website of undeserving honour, as soon as referred to as “probably the most amusing room in Europe”, uncovered as a “website of disgrace” by means of imaginative commissioning and art-making.