Michelangelo (1475-1564) could be essentially the most troublesome Previous Grasp to harness in exhibitions. Getting loans for the greats is at all times troublesome, in fact. However whereas Michelangelo’s physique of labor shares the identical points—shortage, incompletion and polymathy—as Leonardo da Vinci’s, it additionally has one other impediment: scale. And that is doubly fiendish for a present about his later years.

The interval marks Michelangelo’s definitive return to Rome in 1534 and his subsequent tasks for successive popes, patrons and associates. His main works of the time—The Final Judgement within the Sistine Chapel (1534-41), the 2 frescoes for the much less well-known Pauline Chapel close by (1542-50) and the dome of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome—are, plainly, immovable. He made few sculptures, and people, specifically the Florentine and Rondanini pietàs, are unlikely to be lent. So, the curators have given themselves a tough conundrum: how do you replicate the extraordinary achievements of late Michelangelo?

The exhibition affords as a lot tantalisation because it does satisfaction

The reply is thru smaller scale gems and wealthy context. The British Museum’s stellar assortment of drawings types the core of the present, supplemented by glorious loans from elsewhere. However the focus can also be on social and political vicissitudes from the 1530s to the 1560s, and Michelangelo’s place inside them.

A research for the Final Judgment by Michelangelo, made utilizing black chalk on paper (1534–36) © The Trustees of the British Museum

The Everlasting Metropolis was reeling from the Sack of Rome in 1527, when the troops of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, prompted carnage that shocked the papacy and despatched shockwaves throughout Europe. The presence of Europe’s most well-known artist was deemed obligatory as town sought to rebuild its material, its satisfaction and fame. In the meantime, amid non secular turbulence on the daybreak of Protestantism, the delivery of Italian reformist actions and the rising fervour of the Counter-Reformation, Michelangelo contemplated his personal religion.

His rising deal with non secular questions was an inevitable consequence of confronting his personal mortality, which prompted sensible choices about his work, like his collaborations with painters, which the exhibition explores in depth. And with greater than 500 letters to name on, the present and its catalogue go away us with a powerful impression of the person himself: essentially the most well-known artist in Europe, extensively admired, in demand and overworked, but insecure. Few fireworks and showstoppers, then, however an abundance of drawings, letters, poems and books that builds an intimate portrait.

The exhibition is weakest the place it goals for theatre. The audio quotes, in Italian after which English, would possibly wish to bathe the present in mystique and environment however merely obtain a grating, affected croakiness. Nonetheless, rapid irritation rapidly provides option to surprise. We acquire a beautiful sense of Michelangelo’s incomparable technical abilities, whether or not within the briefest of sketches or in worked-up completed designs, but in addition of his use of drawing as a follow for pondering in addition to making: compositions for one challenge cross-pollinate into others, eureka moments rising from play.

Michelangelo’s The Punishment of Tityus (1532) © His Majesty King Charles III 2024

Considered one of his best drawings is right here: The Punishment of Tityus (1532) in black chalk from the Royal Assortment. It illustrates the Ovidian fable of the lustful large punished by being chained to a rock, the place a vulture feasted on his liver for all eternity. The brilliance of Michelangelo’s remedy lies in its incomparable line, beautiful shading and tone within the extra completed areas, the delicacy of the cross-hatching in looser sections, and within the dynamism of its iconography, the place the vulture for Michelangelo turns into a powerful eagle—certainly one of many biggest ornithological drawings in artwork—and Tityus’s physique is described with hot-blooded eroticism. Tommaso de’ Cavalieri, the younger nobleman for whom the drawing was made, and for whom Michelangelo might have been expressing covert need, wrote to the artist that he would research the Tityus and one other drawing for 2 hours every day. And no surprise.

On the verso of the Tityus, Michelangelo ingeniously used the enormous’s pose, turned 90°, as a research for the risen Christ, a theme that obsessed him and finally led to the determine of Jesus in The Final Judgement. A number of extra drawings for the Sistine fresco are included, displaying Michelangelo experimenting with conjuring the vitality of clusters of our bodies, and understanding the exact poses of saints and sinners. A movie accompanying the drawings reveals the fresco intimately and maps the sketches onto exact figures within the last portray. It’s a pity that the identical can’t be achieved for the 2 frescoes within the Vatican’s Pauline Chapel, Michelangelo’s last work, which get brief shrift right here. Fairly merely, barely any research survive; the few which can be listed below are mouthwatering.

Have been there extra, they might illustrate the elevated fervency in Michelangelo’s non secular beliefs, that are explored largely by means of his friendship with Vittoria Colonna, the poet and noblewoman, in whose verse’s non secular passion he discovered a parallel. Colonna was a part of a circle of evangelicals gathered across the English cardinal Reginald Pole, known as the spirituali, whose beliefs echoed a few of the reformist views of Lutheranism. Michelangelo and Colonna exchanged poems and letters however the chief results of their friendship was the present to Colonna of two solemn but spectacular drawings symbolic of their shared religion: the British Museum’s personal Christ on the Cross (round 1555-64) and a pietà on the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston (1540), sadly not within the present.

The drawings for Colonna led to numerous different works and objects, from engravings to paxes and work. The panels should not by Michelangelo himself, however collaborations through which his compositions had been realised in paint by colleagues, most notably within the 1540s and 1550s with Marcello Venusti. The best here’s a crucifixion utilizing Colonna’s Christ on the Cross alongside figures of the Virgin and St John that had been drawn from marvellous separate Michelangelo drawings lent by the Musée du Louvre. Venusti’s work, of which there are a number of, supply fascinating perception into Michelangelo’s course of and the means by which his imagery could possibly be circulated, solely enhancing his fame. However as objects they’re considerably disappointing; the grasp’s drawings are at all times stratospherically superior. One needs Michelangelo had the time and vitality to color the panels himself.

Michelangelo’s Christ on the Cross between the Virgin and St John (round 1555-64) © The Trustees of the British Museum

Maybe essentially the most excessive gulf of this type pertains to the museum’s cartoon, the Epifania (round 1550-53)—Michelangelo’s composition that’s now, by means of conservation, partly launched from the murk that has lengthy bolstered its thriller. A fresco by the artist’s biographer Ascanio Condivi, who was a really restricted painter, hangs alongside the cartoon. It is among the some ways through which the exhibition affords as a lot tantalisation because it does satisfaction.

Nonetheless, there may be a lot to stir and transfer us: examples of Michelangelo’s architectural drawings are testomony to Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s estimation of his forebear’s divinity as an architect, whereas a last, chapel-like room with a number of late crucifixion drawings is completely pitched: a deeply transferring meditation on religion and fragility. The solemn finish to the present is simply enhanced by the presence of his last letters to his nephew and inheritor in Florence, Leonardo Buonarroti.

The curators Sarah Vowles and Grant Lewis have made a superb fist of tackling their not possible process. After all, one of the simplest ways to grapple with Michelangelo’s last 30 years (and far of his earlier life) is to go to Rome and the Vatican. In lieu of that, this present is a good primer.

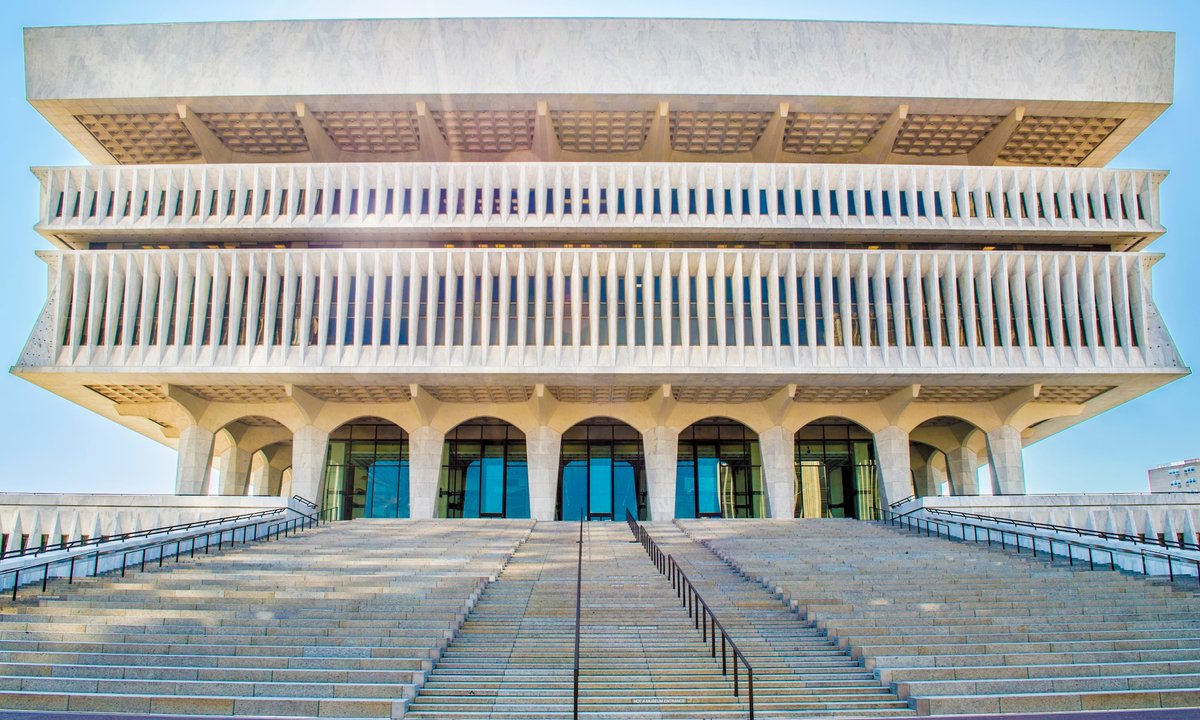

An set up view of Michelangelo: the Final A long time on the British Museum in London © The Trustees of the British Museum

What the opposite critics mentioned

Amongst combined evaluations from British critics, The Telegraph’s Alastair Sooke notes that Michelangelo’s non secular “passion…might shock a secular viewers” however praised the British Museum for not “shying away from Christian content material”. For The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones, the omission of a extra bodily passion—Michelangelo’s sexual attraction to males—is symptomatic of how “a lot enjoyable is excluded”; he says he “discovered it arduous work”. However Michelangelo’s non secular reckoning moved Rachel Cooke, who says “it’s the coronary heart, as a lot because the eyes, that guides you thru its everlasting twilight”.

• Michelangelo: the Final A long time, British Museum, London, till 28 July• Curators: Sarah Vowles and Grant Lewis. • Tickets: £18 (concessions obtainable)