In one in every of Randa Mirza’s images at Les Rencontres d’Arles, a blonde girl smiles and throws a peace signal on the digicam. Behind her is a tank—its lengthy cannon pointing in direction of the highest of her head—in addition to troopers and an aged girl holding a plastic bottle of gasoline.

The scene is uncanny. It brings to thoughts Picture Op (2005), the photomontage depicting former UK prime minister Tony Blair taking a selfie, plumes of fiery smoke behind him, created by the artist duo Peter Kennard and Cat Phillipps as a response to the Iraq struggle. As so occurs, Mirza’s sequence, through which she merges photographs of battle in Lebanon with scenes of leisure, was made at across the similar time.

But whereas the conversations that these works spark—about, for instance, the flexibility of photographs to form our notion of world occasions, and to show struggling into spectacle—should not new, the discourse has not stood nonetheless. A number of exhibitions at this main images competition, held throughout a number of venues within the outdated, picturesque Provençal metropolis of Arles, south-west France, make that clear. They present us how new applied sciences, ideologies and methods of life require us to look afresh on the energy of the picture—and the real-life risks it may well pose.

This begins with Mirza herself. Her present, Beirutopia, locates Lebanon in what she describes as a “multi-dimensional” disaster, struggling to grapple with the after-effects of the civil struggle which ravaged the nation from 1975 to 1990. For the titular work (2010-19), she photographed real-estate billboards positioned “in situ” at building websites across the nation’s capital, as a part of the federal government’s ongoing postwar reconstruction programme. These billboards are idealised, homogenised projections—completely indifferent from Lebanon and its historical past—and their artifice is made clear by the real-life objects that encompass them: pink bricks piled excessive, a glowing orange bollard. What else, the pictures appear to ask, do these shiny illusions cover? What true progress do they impede?

Randa Mirza. The Selective Residence, from the Beirutopia sequence (2019) Courtesy of the artist / Tanit Gallery

France’s Stephen Dock is one other photographer exploring mythologies, this time inside his personal work. In 2011, aged 22 and with out coaching, he travelled to Syria to cowl the civil struggle that had begun to stir there, persevering with on to go to Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon, Lesbos and Macedonia. For his exhibition at Rencontres D’Arles, he interrogates the pictures he produced on this journey, cropping, re-organising and finally annihilating them.

In a single room, he shows a variety in a grid, the locations and dates left off of the captions. Whose tales these are, and the place they start or finish, is misplaced to time and course of. Later, a video set up merges hard-to-read footage drawn from numerous on-line sources—close-ups of mouths talking, explosions, figures wandering a panorama. This was an age when images—and grainy surveillance documentation—started being shared broadly throughout the web, and right here is the confusion that follows.

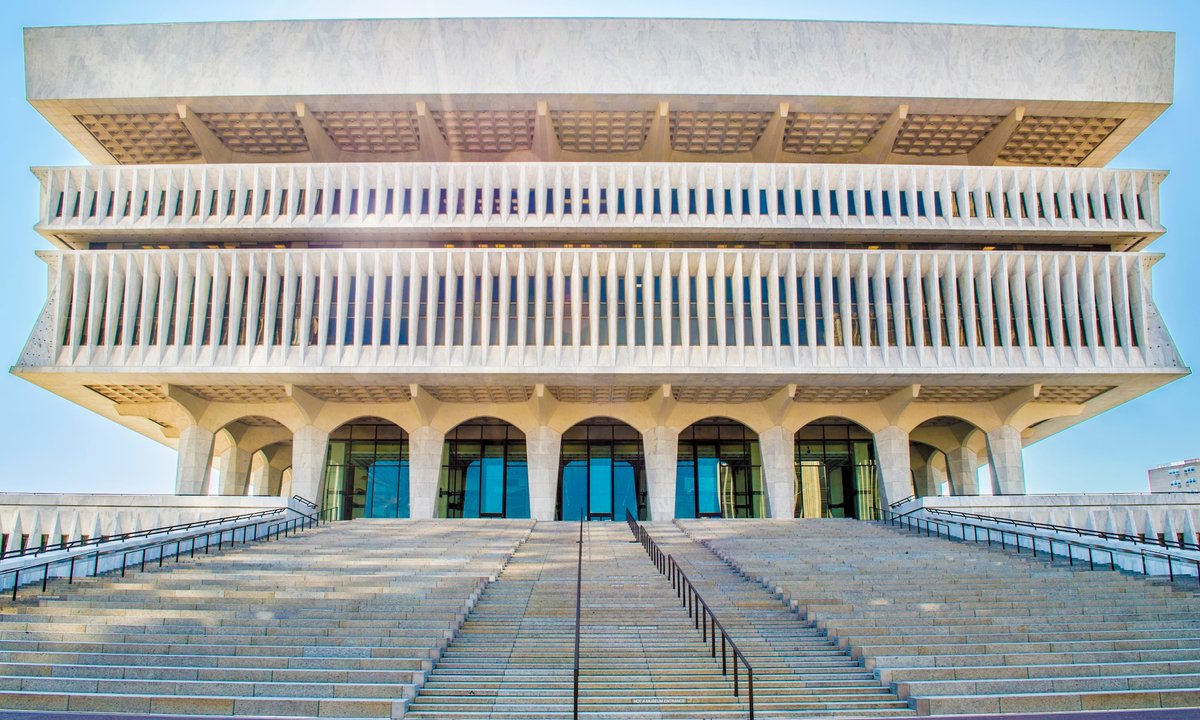

Set up view of Stephen Dock, Echoes sequence (2011-23)

Picture: Luisa Mielenz

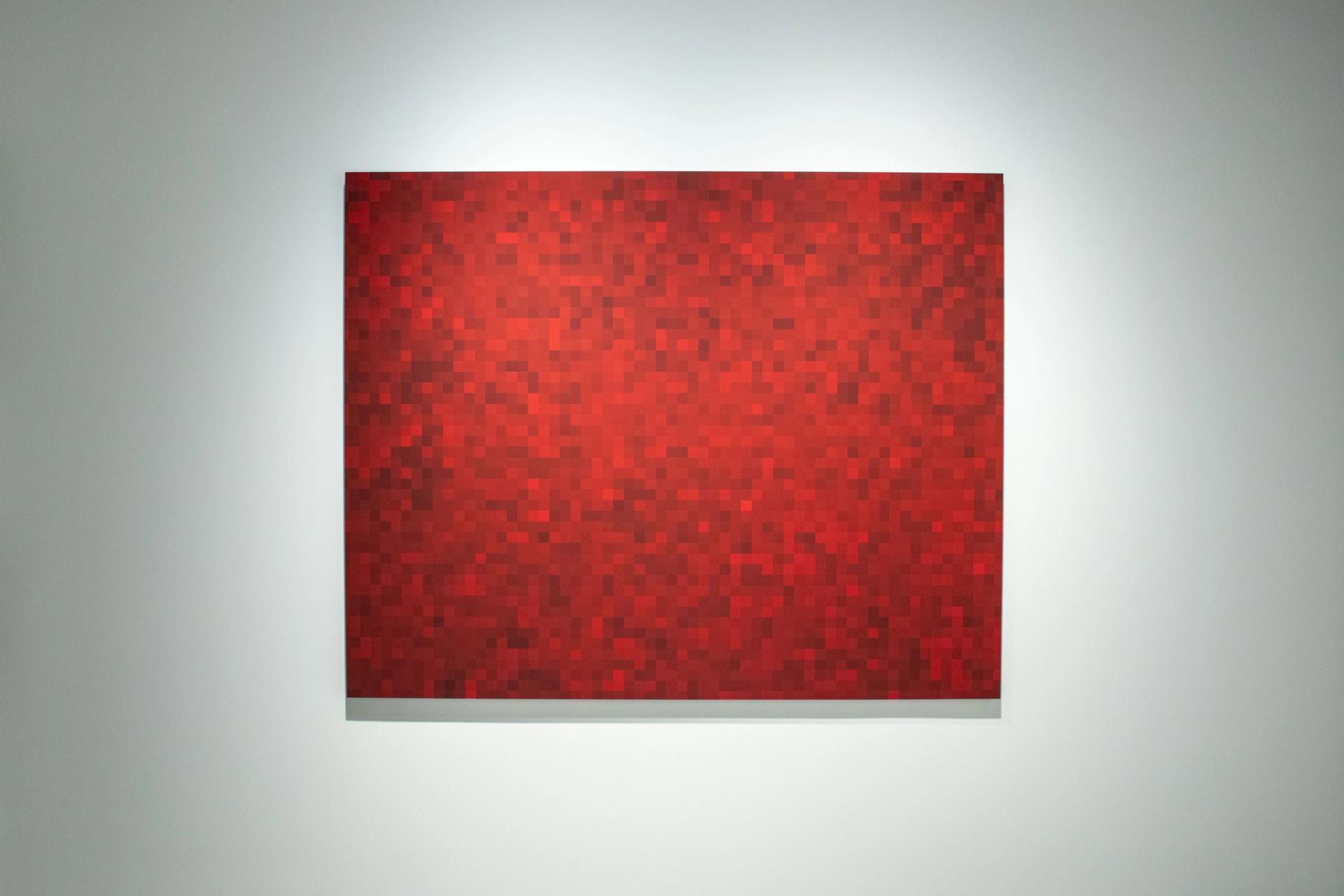

Different works, in the meantime, convey this course of to its pure conclusion: photographs, run by means of a photocopier time and again, disintegrating into nothingness. The ultimate piece is Untitled I (2023), through which illustration has gone and all that’s left is a flurry of blood-red pixels. That is the fallacy of trying to know the world in an image. It can’t be achieved.

Set up view that includes Stephen Dock, Untitled I ) from the Echoes sequence (2011-23)

Picture: Luisa Mielenz

It feels pertinent to see these themes explored in earnest immediately, in a “post-truth” age, the place feelings matter greater than details—and imagery is being manipulated ever extra convincingly to serve political agendas. (Proper-wing, populist events have tended to profit essentially the most from this transformation, and it’s exhausting to disregard that Rencontres d’Arles opened amid a French parliamentary election through which the far proper finally misplaced out on a majority however important features). It’s the post-truth world that the Brooklyn-based photographer Debbie Cornwall zones in on for her contribution to the occasion.

Her present focuses on two our bodies of labor—Mannequin Residents (2024) and Mandatory Fictions (2020)—that spotlight the performative nature of US society, the place actuality and fiction are blurred. Most of the photos are surprising. That is very true of units of photographs taken at army and border patrol coaching camps throughout the nation—amongst them “Atropia”, a pretend nation crammed with mock Iraqi and Afghani villages. Within the images, troopers grin on the digicam, their faces lined in pretend wounds; figures kneel, palms tied behind their again; and residents of Iraq and Afghanistan stand wearing costume, employed as actors. Many who participate, the wall textual content explains, are struggle refugees.

Set up view of Debi Cornwall, Mannequin Residents, that includes photographs from the sequence Mandatory Fictions (2020)

Picture: Luisa Mielenz

A movie set up tells a narrative, by means of a montage of Hollywood movie clips overlaid with courtroom testimonies, through which a soldier was killed as a result of he mistook a police officer to be a fellow participant in a single train. Different photos, in the meantime, depict Make America Nice Once more supporters standing drenched in paint, and one man dragging a large US flag throughout our eye line. We reinforce fictions, visually and bodily, this exhibition reminds us, in our each day lives. These are the pictures we make for ourselves—and the results are well-known.

Debi Cornwall, Flagraising, “Save America” rally, Miami, Florida, US, from the Mannequin Residents sequence (2022)

Courtesy of the artist

None of those reveals proffer a solution to the questions they pose—certainly, how might they? However what is maybe the closest to at least one comes from an sudden supply.

In When Photos Be taught to Converse: Conceptualised Documentary Images from Astrid Ullens de Schooten Whettnall’s Assortment, an exhibition at Luma Arles, the textual content reads: “The muse’s assortment… testifies to a different essential fact: whereas it recognises that the only picture could be lovely, even nice, it additionally is aware of that it says surprisingly little concerning the world.”

What follows are a sequence of groupings that, collectively, converse of the ability of multiplicity, of nuance and looking for the larger image. In an more and more fractured, frightened world, that is one thing we might all do with maintaining on the prime of our minds.

Rencontres d’Arles runs till 29 September