This month, London audiences may have a mouthwatering encounter with a Fashionable grasp whose impression on up to date artwork has been huge. However the venue isn’t Tate Fashionable. It’s the Royal Ballet and Opera, which hosts Three Signature Works, a trio of items by George Balanchine, elegant choreographer of the Fashionable period: Prodigal Son, first carried out in 1929, Serenade (1935) and Symphony in C (1947).

Balanchine pioneered “neoclassical” ballet, so-called as a result of it makes use of conventional strategies for radical new choreography. His profession is startling within the eras that it straddled, the modernities it witnessed and formed, and the avant-garde protagonists who populate it.

Born Georgi Melitonovitch Balanchivadze in St Petersburg in 1904 (he died in 1983), by 21 he was working with Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, revising Léonide Massine’s 1920 choreography of Stravinsky’s Le Chant du Rossignol, with Henri Matisse’s unique costumes and units. He by no means regarded again.

Landmark trio

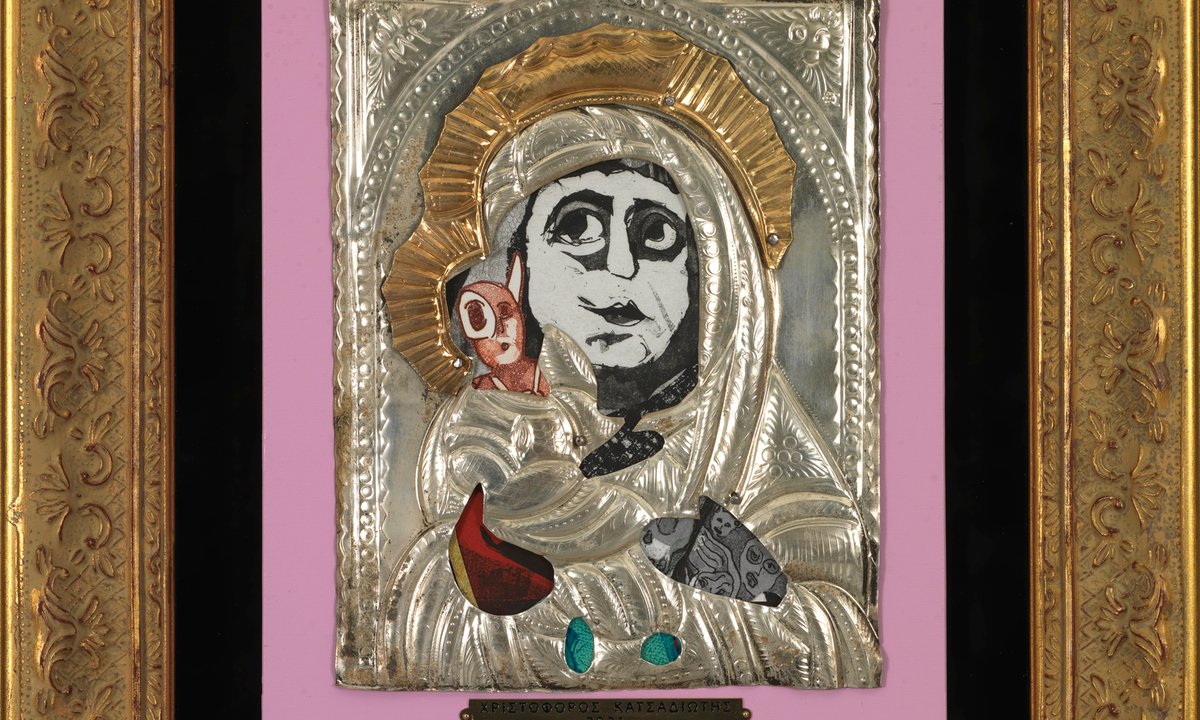

The three works being carried out in London are all landmarks. In 1929, The Prodigal Son premièred as the ultimate Ballets Russes ballet, as Diaghilev died later that 12 months. The units and costumes have been designed by the French painter Georges Rouault, a someday Fauve obsessive about spiritual iconography. Artist and choreographer discovered a selected symbiosis of their fascination with the readability and ease of a historic kind: “In designing the choreography,” Balanchine stated, “I had in thoughts the Byzantine icons which might be so acquainted to all Russians.” Rouault’s designs might be revived for the Royal Ballet efficiency.

Serenade was the primary ballet Balanchine choreographed within the US. Created on college students on the College of American Ballet (and, radically, together with errors and probability moments), it’s central to the repertoire of the New York Metropolis Ballet (NYCB), which Balanchine co-founded in 1948. Its creative historical past, with designs by the minor artist Gaston Longchamp, is maybe much less distinguished. However Symphony in C’s unique manufacturing (then known as Le Palais de Cristal) concerned a serious artist from the outset, with designs by the Surrealist Leonor Fini. Her costumes, themed across the colors of gems, finally additionally knowledgeable new Balanchine choreography; a 1967 piece, Jewels.

Generations of affect

Within the US, Balanchine each influenced and prompted extra irreverent response amongst successive generations of choreographers, like Yvonne Rainer and Merce Cunningham, and their wider creative milieux. That he integrated Summerspace, the nice 1958 Cunningham collaboration with Robert Rauschenberg, into the NYCB repertoire, is telling of his appreciation of his followers.

However Balanchine’s relevance to visible artwork is not only in direct collaborations and affiliations with artists in his lifetime. His formal gestures and patterns make him essential to sure strains of up to date efficiency artwork. Key to the choreographic floor that he broke was its plotlessness. “A ballet might comprise a narrative, however the visible spectacle, not the story, is the important ingredient,” he stated, including: “The choreographer and the dancer should keep in mind that they attain the viewers by the attention—and the viewers, in its flip, should prepare itself to see what’s carried out upon the stage.”

He insisted on an summary visible urgency whereas empowering his viewers

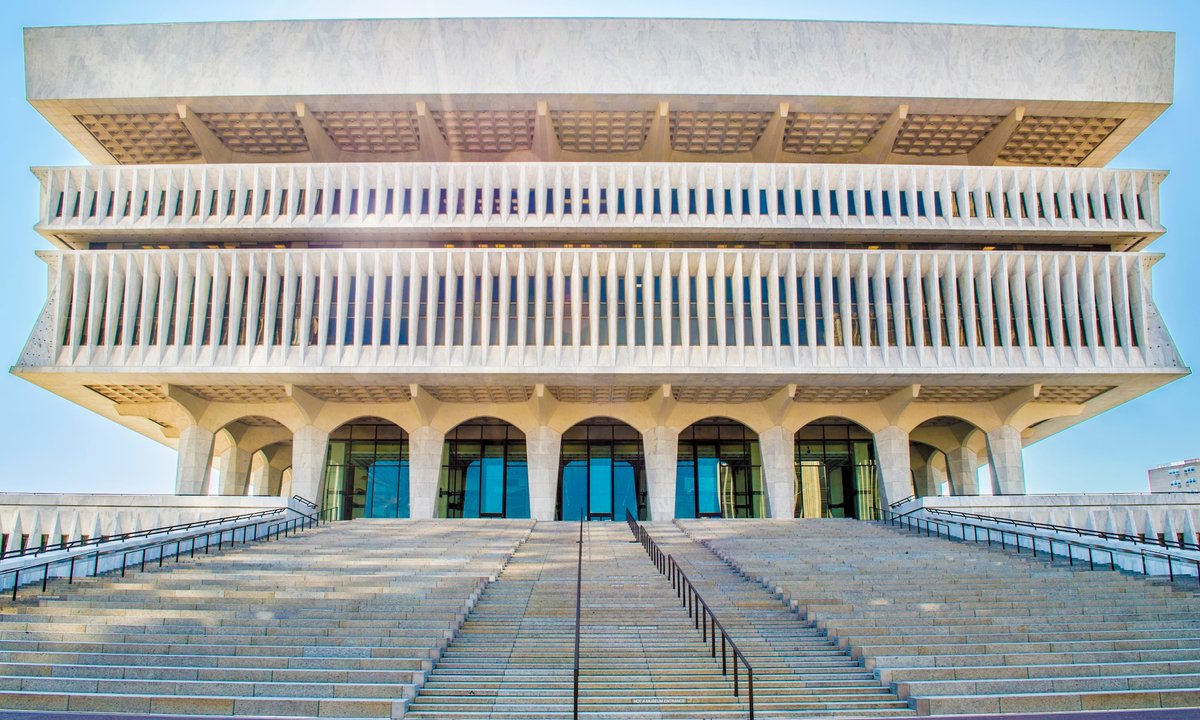

So he each insisted on an summary visible urgency whereas empowering his viewers—a profoundly up to date ideally suited. And artwork has moved steadily in the direction of Balanchine’s self-discipline over latest a long time, dissolving boundaries between efficiency and sculpture, gallery and stage. The artists Tino Sehgal and Pablo Bronstein, as an illustration, have used Balanchine’s actions inside performative collages in gallery settings. Sehgal integrated Balanchine’s steps inside his early work 20 Minutes for the twentieth Century (1999), a “museum of dance”, as he described it. Bronstein integrated Balanchine’s actions into items for the Performa Biennial in 2007 and the Duveen Fee at Tate Britain in 2016, wherein he riffed on dance’s relationship to structure.

These mirror a preoccupation with museums as areas activated by our bodies, greater than merely as shows of objects. In 2015, the artwork historian Dorothea von Hantelmann argued that “within the canon of the twenty first century”—one in all “a historical past of bodily postures and types of embodiment”—Balanchine might be “as vital as Malevich”. As artists grapple with this concept and problem and reinvent the museum, the stability of grace and economic system in Balanchine’s choreography, and its personal engagement with cultural traditions, affords an irresistible eloquence.

• The Royal Ballet presents Balanchine: Three Signature Works as a part of Dance Reflections by Van Cleef & Arpels, 12 March-8 April, www.dancereflections-vancleefarpels.com