On the quilt of Weegee: Society of the Spectacle are two self-portraits of this enigmatic, larger-than-life photographer. Within the first, resembling a felon’s mugshot, Weegee offers a tough stare down the lens, brandishing a flash-bulb digital camera, his trademark lengthy cigar protruding from his puckered lips. The second is distorted like a wavy enjoyable home mirror, warping the photographer right into a goofy, bug-eyed caricature. That these two photographs are taken by the identical photographer hints on the paradox of Weegee’s work. As he urged himself throughout an interview in 1965: “My actual title is Arthur Fellig. However I don’t even recognise it once I see it. I created this monster, Weegee, and I can’t do away with it. It’s like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde.”

Weegee is greatest recognized for his tabloid photographs of New York Metropolis within the Nineteen Thirties and Nineteen Forties—unflinching images of gangsters, blood-stained crime scenes, deadly accidents and fires—and his repute as a savvy industrial operator and a significant social documentarian of the mid-Twentieth century is all however cemented. Far much less celebrated (certainly, usually derided) are his later images produced in California and Europe. Created, notes Clément Chéroux, director of the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris, “with the assistance of a capacious bag of technical tips”, Weegee’s satirical photographs of Hollywood celebrities and worldwide politicians appear to be the work of a distinct photographer altogether. Printed for an exhibition of the identical title at New York’s Worldwide Middle of Images (ICP), residence to the Weegee Archive, Society of the Spectacle makes an attempt to realign these two apparently contradictory our bodies of labor, emphasising Weegee’s curiosity within the nature—and the tradition—of the spectacle.

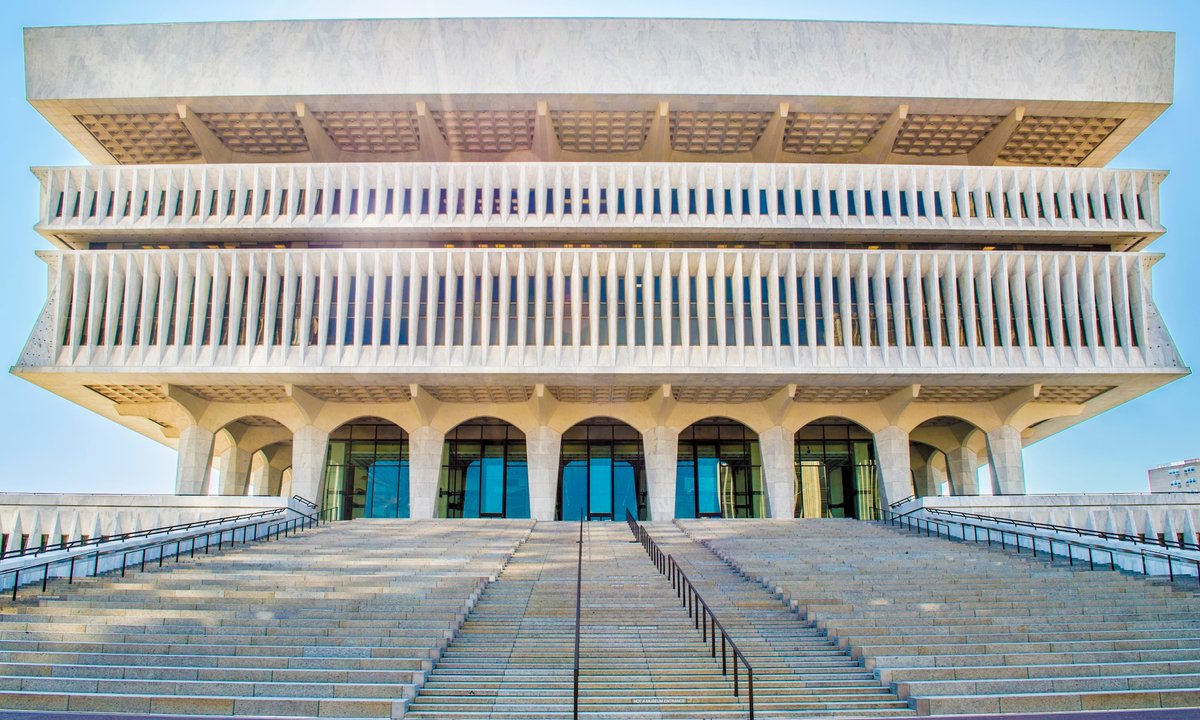

Weegee on the Typewriter within the Trunk of the 1938 Chevrolet, New York (round 1943) © Weegee Archive/Worldwide Middle of Images, New York

Born in Zolochiv (Ukraine) in 1899, Fellig emigrated to the US in 1910, leaving college at 14 to assist his household by working odd jobs, together with as a darkroom assistant on the New York Occasions. In 1935 he lastly turned freelance, aided by a shortwave radio tuned to the frequency of the Manhattan Police Division, permitting him to be among the many first to reach on the scene: Fellig’s pseudonym, he claimed, was derived from the Ouija board, testifying to his apparently clairvoyant capability to know each when and the place town’s subsequent crime would happen. “Individuals wanting on Weegee’s unimaginable images for the primary time,” wrote William McCleery in his topic’s first images guide, Bare Metropolis (1945), “discover it laborious to imagine that one strange earth-bound human being may have been current at so many climactic moments.”

There is no such thing as a denying the specific nature of Weegee’s tabloid images, depicting blood-soaked streets and gunned-down corpses, crumpled automobiles and scenes of desperation. “I Cried Once I Took This Image”, reads a well-known caption to his {photograph} of a mom and her daughter witnessing their family members succumbing to a blazing hearth. Weegee’s physique rely is sizeable, with no try to hide the brutality of what’s proven. In actual fact, illuminated by his flash, Weegee’s images are distinctively crisp and brightly lit, as if intentionally exposing the fact of New York’s nocturnal underworld: a type of forensics. It makes for a sobering reflection on the present state of picture circulation that Weegee’s photos, regardless of their graphic contents, don’t seem extra surprising. “The {photograph} offers combined alerts,” writes Susan Sontag in Relating to the Ache of Others (2003). “Cease this, it urges. But it surely additionally exclaims, What a spectacle!”

Weegee’s curiosity within the spectacle is obvious from images through which the scenes of homicide and catastrophe type a theatrical backdrop to crowds of onlookers and passers-by. Balcony Seats at a Homicide (1939) captures dozens of heads looming from tenement home windows for a view of the physique beneath. Most putting of all is the Brooklyn college woman on the coronary heart of Their First Homicide (1941), wide-eyed and craning her neck for a glimpse of atrocity.

Weegee presents a comic book commentary on fame and its distortions lengthy earlier than the age of smartphone filters

Named after the French theorist Man Debord’s seminal essay of 1967, Society of the Spectacle efficiently makes the case for the American photographer’s later photos, an extension of his curiosity in a tradition preoccupied by visions of itself. Reworking well-known faces into grotesquely pinched and bloated caricatures, from Marilyn Monroe and Chairman Mao—predating Warhol’s well-known silkscreens—to Charlie Chaplin and Salvador Dalí, Weegee’s “magic” photographs supply a comic book commentary on fame and its distortions lengthy earlier than the age of smartphone filters.

The publication features a uncommon sequence of Weegee’s images from the set of Stanley Kubrick’s characteristic movie Dr Strangelove (1964), depicting forged members ballooned into bulbous gargoyles by a fish-eye lens. “Though these photographs are helpful paperwork of the genesis of Kubrick’s movie,” writes the curator David Campany in a brand new essay included right here, “they’re additionally supremely ‘Weegee’ images, filled with loopy incident, surprising tenderness, black humour, and unusual magnificence.”

• Clément Chéroux, Cynthia Younger, Isabelle Bonnet, David Campany, Weegee: Society of the Spectacle, Thames & Hudson, 208pp, 130 illustrations, £45 (hb), printed 9 January

• Rowland Bagnall is a author and poet. His new assortment, Close to-Life Expertise, was printed by Carcanet Press in 2024