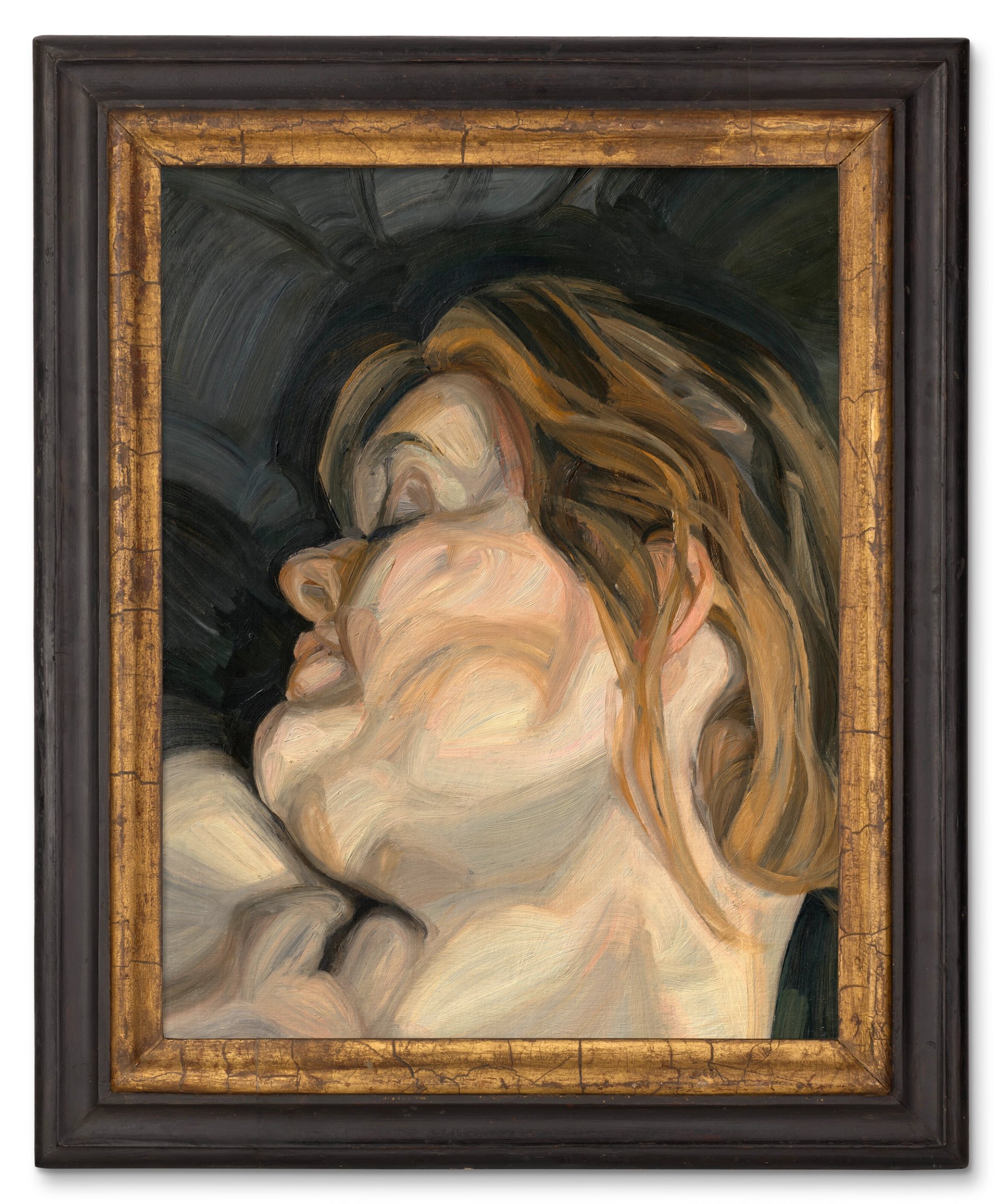

Christie’s will promote three early Lucian Freud work from the identical assortment in its London night sale on 15 October, with a mixed estimate of £13m to £20m.

The works present Freud’s model evolving over three a long time: from the crystalline rigidity of the wartime Girl with a Tulip (1944), to Self-portrait Fragment (round 1956), painted as his marriage was dissolving, to the bolder fluency of Sleeping Head (1961–71).

The work have all been in the identical non-public assortment for a few years and, though Christie’s declines to touch upon the id of the proprietor, the works are at present in free circulation within the UK. They’ve all been exhibited broadly in main exhibits such because the touring exhibition Lucian Freud: Work (1987–88), which travelled to Washington, Paris, London and Berlin, his Kunsthistorisches Museum retrospective in Vienna in 2013, and Lucian Freud: New Views, on the Nationwide Gallery, London and the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, in 2022-23.

Lucian Freud, Girl with a Tulip (1944)

Courtesy Christie’s Photographs 2025

Girl with a Tulip (1944, est. £3m-£5m) depicts Lorna Wishart, whom Freud described as “the primary one that meant one thing to me”. Wishart, the famously lovely youngest Garman sister and the aunt of Kitty Garman, who later turned Freud’s spouse, additionally seems in one other of Freud’s works, Girl with a Daffodil (1945), now within the Museum of Trendy Artwork in New York.

Exactly painted with the sable brushes Freud favoured in his youth, this icon-like portray was exhibited in Freud’s first solo present on the Lefevre Gallery in 1944 and, in its stillness, depth and use of iconography, is clearly a stylistic precursor to well-known work comparable to Woman with a Kitten (1947) and Woman with Roses (1947-48). It has been within the vendor’s assortment because it was purchased from Freud’s seller and agent James Kirkman in 1995.

“This image feels fairly devotional, as opposed the later portray of Lorna [in Moma], which exhibits how the connection had soured,” says Katharine Arnold, the vice-chairman twentieth/twenty first century artwork, and head of post-war and modern artwork, Europe at Christie’s.

Freud had moved on by the point he painted Self-portrait Fragment (round 1956, est. £8m-£12m), an equally intense however bigger work painted within the non finito custom, which was first proven at London’s Marlborough Gallery in 1968, the place the seller purchased it (the Kunsthistorisches Museum retrospective in 2013 was the primary time it was seen in public for 45 years). Within the mid-Nineteen Fifties, Freud had simply transitioned to utilizing thicker, hog’s hair brushes and was spending a number of time with Francis Bacon—within the 2022-23 Nationwide Gallery exhibition, this work was hung subsequent to his portrait of Bacon, portray in 1956–57.

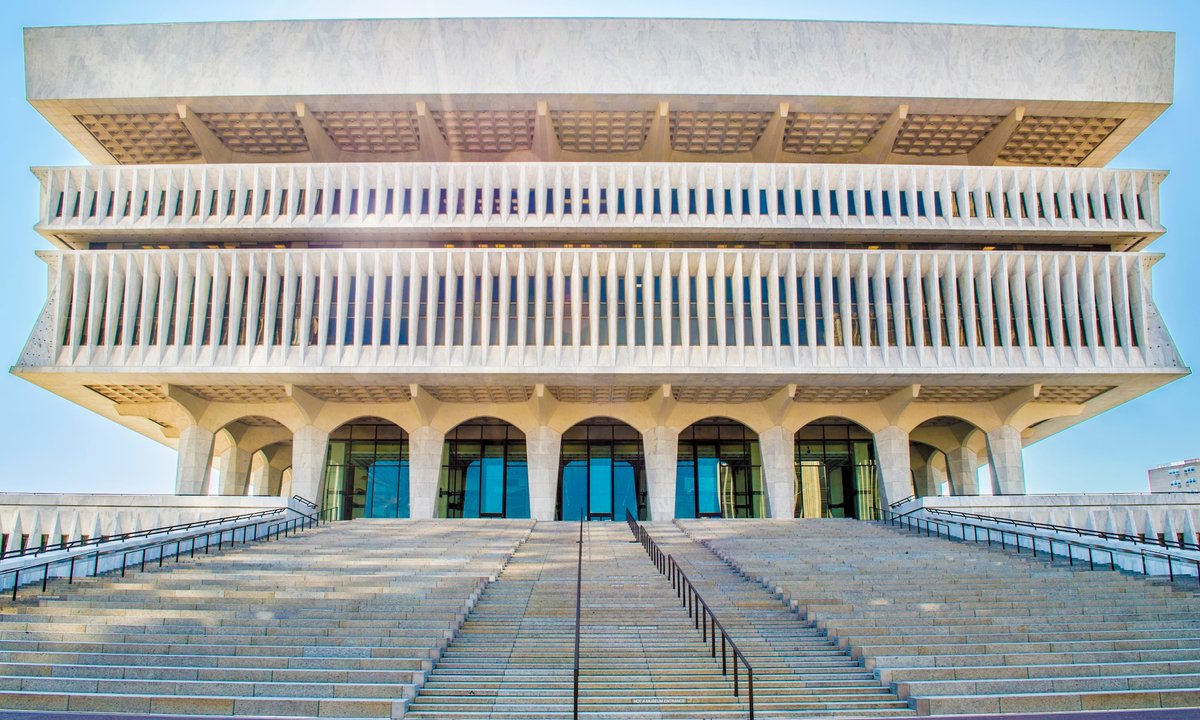

Lucian Freud, Sleeping Head (1961-71)

Courtesy Christie’s Photographs 2025

“Already by 1956, you’re an older man—Freud is in his 30s and he’s fascinated with how paint might change, the way it might start to loosen up,” Arnold says. “At this level, Bacon has an necessary affect over Freud’s follow and it’s with some encouragement from Bacon that Freud decides to loosen up his brushwork. There’s a narrative that, within the early interval, Freud stated he would generally see the define of his eye on the canvas as a result of he was staring so exhausting. However by 1956-7 he has began to loosen up.” She provides: “Freud is just not us on this image, he’s himself. His relationship along with his then spouse Caroline Blackwood is altering, he’s not within the first flush of affection.”

The brushstrokes get thicker and extra expressive nonetheless in Sleeping Head (1961–71, est. £2m-£3m), the one one of many trio to have beforehand appeared at public sale—at Christie’s London in 1971, when it was offered by the fifth Marquis of Dufferin and Ava, Sheridan Dufferin, Blackwood’s brother. First proven at Marlborough Gallery in 1963, the tightly cropped work depicts a younger lady, who met Freud in a Soho bar, dozing on the oft-depicted shabby leather-based couch in his Paddington studio.

“This portray marks one other transition in approach once more,” Arnold says. “At this level he has simply come again from Greece and he has a quick relationship with this lady. We don’t know who she is, however he’s portray in a really free, assured means. We don’t know if that’s a mirrored image of his private life—he’s not married—however he’s now getting into a really fluent, simple portray model. So, once you have a look at all three works collectively, you may have this arc of portray approach.”

In the marketplace for Freud’s work, Arnold says: “There’s a excessive diploma of curiosity within the early works, the reason is that after 1958 the approach has modified so there’s solely a discreet second in time when these works have been being made, due to this fact they’re uncommon, particularly as a number of the good early work are in public establishments.” She provides: “I feel the consumers of those early works would possibly simply as simply be the client of a 1932 Picasso—they’re not essentially the type of one that would purchase a British figurative painter.” The sitter additionally performs a task in a works attraction and, Arnold provides, “a self-portrait is all the time a very fascinating perception right into a painter, in order that they are typically essentially the most prized—we’ve got collectors who solely purchase self-portraits.”

As for geographical demand, Arnold says: “Over the previous 12 months, we’ve offered a significant portray to North America, two to Asia, we’ve had deep European bidding, UK consumers. So, it’s common.”

The work have been assured to promote by Christie’s.