Nothing sits nonetheless in Jan van Kessel’s photos. Dotted with amber-flecked beetles and marbled moths, the Flemish painter’s oils stir with life. In them, butterflies—some lemon yellow, others pearl gray and daubed with inexperienced—perch on rosemary leaves. Velvety bumblebees tiptoe over paper-thin blossoms. If bugs, because the English naturalist Thomas Moffett wrote in 1590, are for the “delight of the eyes” and the “pleasure of the ears”, then these photos are pure pleasure.

Arrayed within the Nationwide Gallery of Artwork present Little Beasts: Artwork, Surprise and the Pure World, in Washington, DC, are work and prints by Van Kessel and Joris Hoefnagel, amongst others, from Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-century Europe, when increasing commerce routes introduced the examine of nature—and nature as artwork—to new heights. Within the Flemish port metropolis of Antwerp (its harbour as soon as dubbed the market of “all the universe”), Hoefnagel and Van Kessel responded to the surge in demand, inflecting their photos with black- and silver-quilled porcupines, fire-red salamanders and checkered caterpillars, all with a studied delicacy. Right here, the minute is monumental.

Hoefnagel travelled extensively, fixing his gaze on the small and complicated. As a luxurious service provider, he ventured to France and Spain, of which he famous: “He who has not witnessed Seville has not witnessed miracles.” Artwork lovers in Europe commissioned photos of their very own acquired miracles or cupboards of curiosity. And the curiosity ran deep. Hoefnagel made 300 watercolour miniatures for one collection, and Van Kessel’s oeuvre included greater than 700 works.

Jacob Hoefnagel (after Joris Hoefnagel), Half 1, Plate 1, from the collection Archetypa studiaque (Archetypes and Research), 1592 Courtesy the Nationwide Gallery of Artwork, Washington, DC

What’s most placing about these photos, set in opposition to the gallery’s pistachio and brick-red partitions, is their masterful element. Hoefnagel works with a surgeon’s precision, drawing out every cell of a dragonfly’s gossamer wing, its lime-green physique awash in liquid-black abstraction. To his tortoiseshell butterfly, he added touches of gold; to fish scales, gauzy silver paint. In a single image, Van Kessel signed his title in feverish-red caterpillars and emerald-scaled serpents, jewel-like spiders hanging down, tauntingly, over the portray’s edge.

To be that attentive to nature, to let the world wash over you, appears a selected form of present. In the identical approach one loses the practice of a dialog when immediately fixating on one thing lovely, Hoefnagel and Van Kessel appear to linger within the very act of wanting. There’s a tenderness to this work, an intimacy. “Keep some time,” they appear to induce. “Go on wanting.”

Their attentiveness had a non secular posture too. These photos have been a reminder of divine windfall, of God’s grace made manifest. Because the English naturalist John Ray wrote in 1691: “If man must replicate upon his Creator the glory of all his works, then ought he to take discover of all of them, and never suppose any factor unworthy of his cognizance.”

Time spent observing isn’t wasted. Think about Hoefnagel’s elephant beetle, sinuous and copper-dappled, its horn curved like a thick eyelash. It sits under an inscription from the Ebook of Psalms: “The concern of the Lord is the start of knowledge.” It’s from that vantage level—low to the bottom and seeing the world anew—that these artists delighted in nature and its splendours. The elephant beetle, believed on the time to have originated from its personal ashes, evoked Jesus Christ’s resurrection—as did the butterfly, rising from a cocoon right into a state of winged brilliance. (Moffett wrote that the butterfly’s sapphire wings can “disgrace the peacock”.)

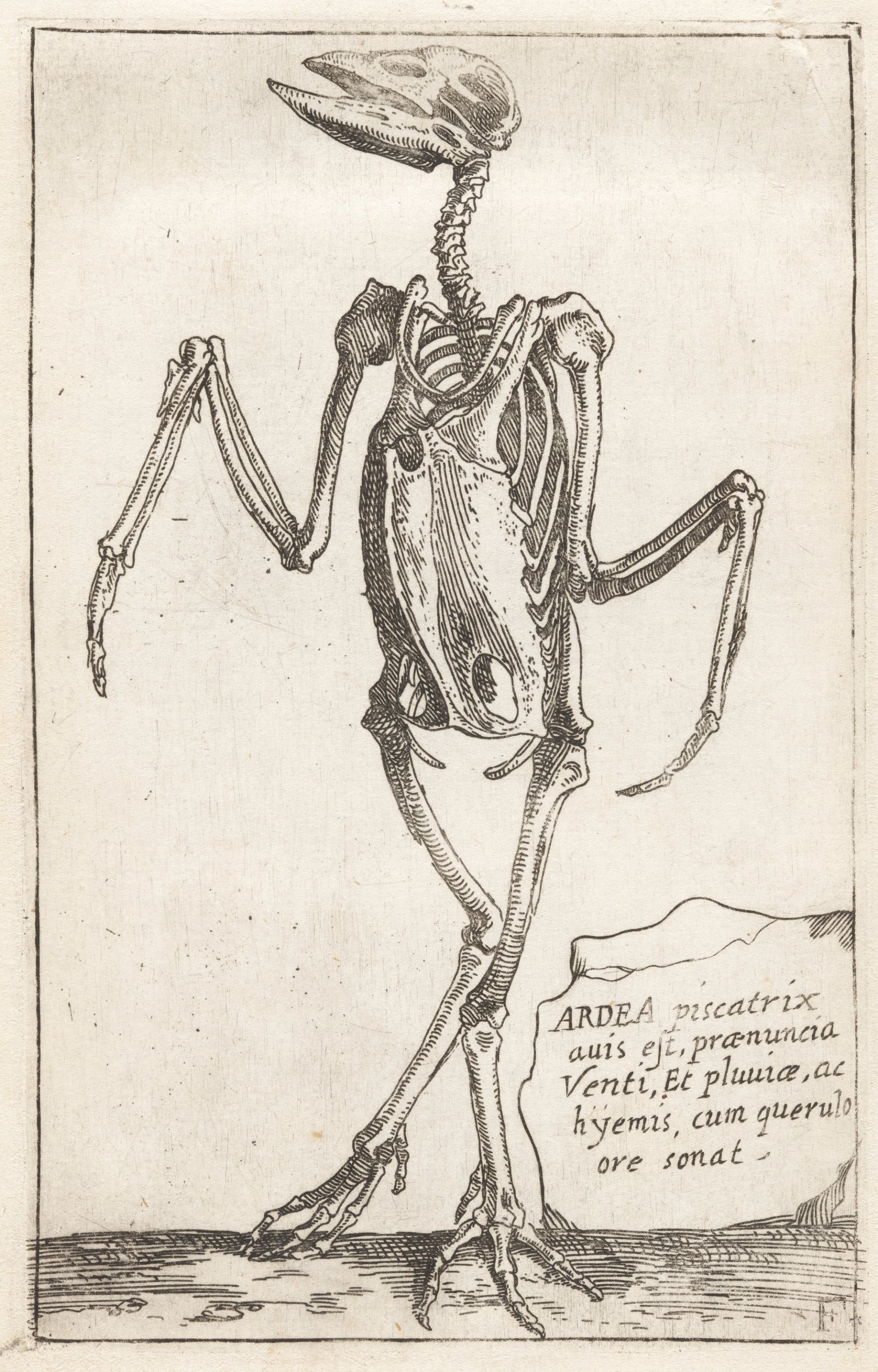

Teodoro Filippo di Liagno, Skeleton of a Heron, from the collection Animal Skeletons, 1620–21 Courtesy the Nationwide Gallery of Artwork, Washington, DC

Disgrace runs all through the present, too, tinging it with a pathos that hangs flippantly, by no means feeling like a burden. Take the Neapolitan artist Teodoro Filippo di Liagno’s collection of etchings of animal skeletons. One, of a heron, is rigorously attended to—its needle-sharp limbs sloped inwards like a ballerina at relaxation. The souvenir mori appears weightless, suspended in time. One will get the sense that even the macabre right here was finished in a spirit of playfulness. As Jacob Hoefnagel, Joris’s son, inscribed on one among his father’s photos, the work is “freely communicated in friendship to all lovers of the Muses”. Love abounds in all these works.

One of many last items within the present is Van Kessel’s Noah’s Household Assembling Animals Earlier than the Ark (round 1660). Strewn with tomato-red parrots and turkeys ringed in charcoal, it’s a work of shut examine, of concern giving strategy to hope. The flood is at hand, however Van Kessel privileges magnificence, unfettered. There shall be hardship, it pronounces, but additionally sublimity, one thing wondrous and past creativeness.

The luxurious essays of the American naturalist John Burroughs come to thoughts. In a single, he recollects the fun of catching a bee in his hand: “Although it stung me, I retained it and regarded it over, and within the course of was stung a number of occasions; however the ache was slight.”

Little Beasts: Artwork, Surprise and the Pure World, Nationwide Gallery of Artwork, Washington, DC, till 2 November