An inoperable silvery-blue bus is parked at a dying Greyhound Strains terminal in Cleveland, Ohio, and it’s changing into a beehive of exercise.

Its presence has stirred up “so many various feelings”, says Robert Louis Brandon Edwards, an historian, artist and preservationist primarily based in Cleveland. Final yr, he purchased the bus, which was manufactured for Greyhound in 1947, and had it trucked from a Pennsylvania junkyard to Ohio.

The bus station, in-built 1948, is a Streamline Moderne masterwork by the architect William Strudwick Arrasmith (1898-1965), with hairpin curves and silvery-blue tiles resembling the fleet that when handed by it. The station will shutter late this yr as Greyhound sheds its real-estate portfolio amid trade decline. Plans are afoot to recycle the station into public area for its new proprietor, Playhouse Sq., an adjoining nonprofit compound of century-old efficiency venues.

Edwards, in collaboration with Playhouse Sq., is changing his automobile right into a museum of the Nice Migration—when, between roughly 1910 and 1970, thousands and thousands of African Individuals moved out of the agricultural South to the Northeast, Midwest and Western US. With exhibitions and virtual-reality experiences, the brand new museum will convey what folks endured on their journeys northward, escaping from Jim Crow segregation and brutality.

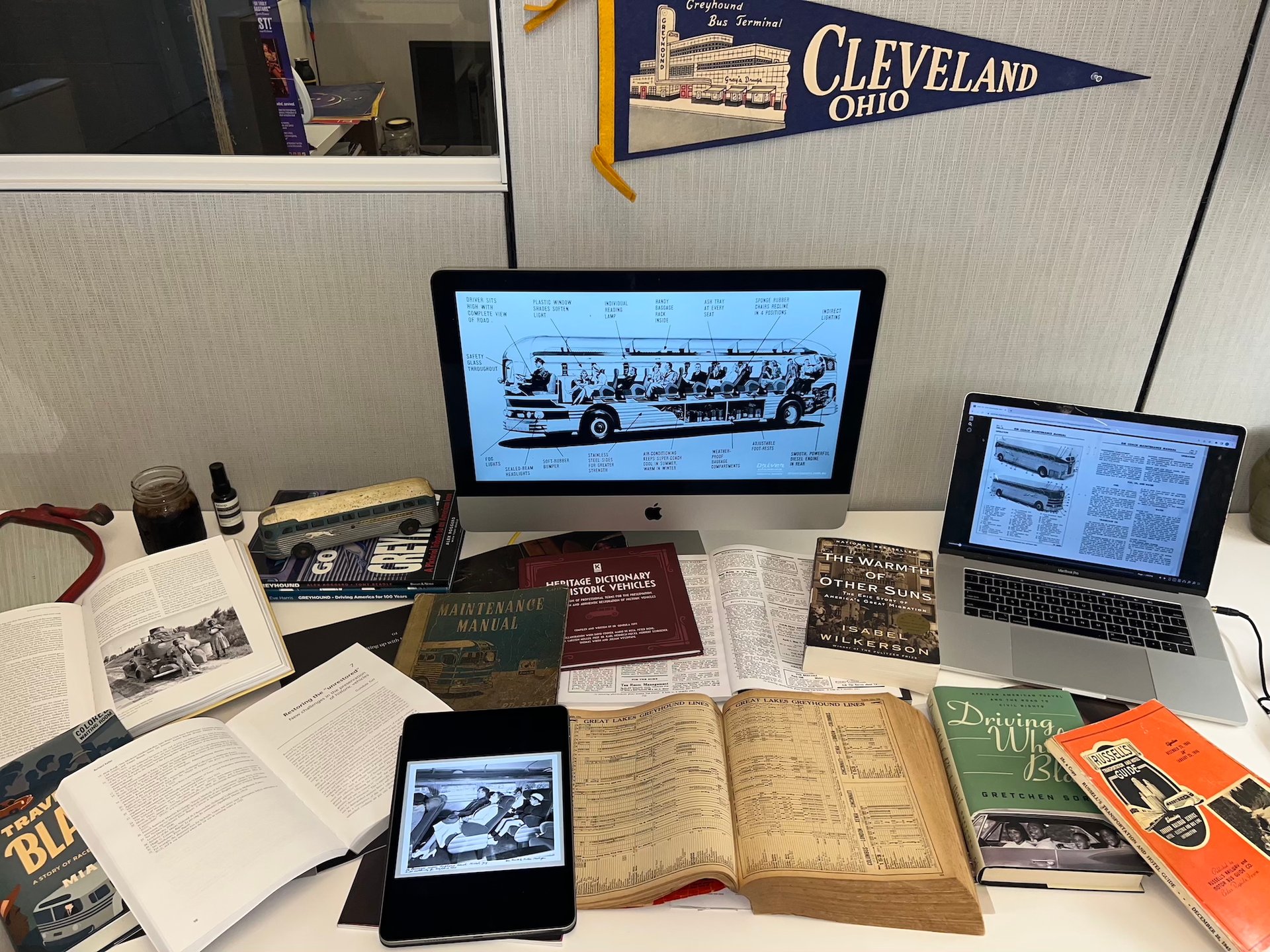

Edwards and his Greyhound Photograph: Leo Michael Nash

Edwards is gutting the bus’s inside (within the Nineteen Seventies, it was become a house on wheels with an orange kitchen, toilet and sleeping quarters), whereas giving lectures and bus excursions. He’s amassing artefacts—resembling Greyhound route maps, timetables and ads—and interviewing veterans of Nice Migration passages and their households. He’s even documenting reactions from perplexed travellers and staff to his bus, berthed within the station’s again lot.

One frequent query: “Is that this the bus that Rosa Parks rode when she was arrested?” (No, that one is restored and parked indoors on the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.) One frequent remark: “I by no means considered how my ancestors bought to Cleveland. It might need been on a bus like this; I’m wondering if there’s anybody left to ask.”

Black passengers within the mid-Twentieth century had been usually crammed into buses’ dimly lit again rows atop grinding sizzling engines, Edwards says. They risked being harassed, assaulted, dragged away or worse. They introduced alongside stockpiles of their very own meals, reasonably than hoping that roadside eating places would welcome them. “They didn’t know which locations had been protected for them to make use of,” he provides. “Greyhound bus stations, to me, are like Ellis Island.”

The challenge, which is a part of Edwards’s Columbia College doctoral research in historic preservation, was impressed by his family’s odyssey. In 1963, his grandmother Ruby Mae Rollins moved by Greyhound bus from Fredericksburg, Virginia, to Manhattan along with her small daughters Cindy and Linda (Edwards’s mom). Cindy Rollins, who has retired from a profession in training in New York and moved again to Fredericksburg, says that she remembers her mom supplying consolation meals in the back of the bus: “She fed us along with her hen from house.”

Edwards’s challenge is a part of his Columbia College doctoral research in historic preservation Photograph: Leo Michael Nash

In 2022, Edwards began questioning whether or not any bus used in the course of the Nice Migration survived, for him to revive and share its story. His considering was alongside the strains of: “Hey, that’s a loopy thought, I ought to most likely pursue that,” he says. When an acceptable vintage surfaced in Pennsylvania, priced at $12,000, he bargained the junkyard proprietor all the way down to $5,500 in money. (Transport the automobile by flatbed truck to Cleveland, with a pitstop at Cindy Rollins’s driveway in Virginia, value $7,000.) Many authentic bus elements survived the Nineteen Seventies redo, together with the again bench utilized by Black riders and the vacation spot signal over the windshield fabricated from a roll of black-and-white material.

Final yr, Playhouse Sq. paid about $3m for the Greyhound terminal, and Edwards requested to shelter his bus there. The nonprofit’s staff jumped on the likelihood to include his compelling challenge into reuse plans for the station, says Craig Hassall, Playhouse Sq.’s president and chief govt: “The synchronicity is palpable.” Programmes and shows on the transformed constructing could discover associated elements of Ohio’s historical past, together with its Nineteenth-century stations for Black escapees on Underground Railroad strains and the Jazz Age performers and ticket-holders who took buses to achieve Playhouse Sq.’s gilded neoclassical theatres.

Regennia N. Williams, an affiliate curator on the Cleveland Historical past Heart, says that Edwards’s shocking bus-in-progress is sparking admiration for its tenacity. He has turn out to be recognized domestically as “a little bit of a folks hero,” she says. This autumn, the centre’s new gallery devoted to the realm’s African Individuals will cowl matters together with Nice Migration arrivals.

Amongst different establishments exploring the topic is the Marin Metropolis Historic and Preservation Society in northern California, which organises travelling exhibitions in regards to the area’s Black staff who arrived within the Nineteen Forties for jobs at army shipyards. The society shows a restored Nineteen Forties Greyhound bus (owned by the close by Pacific Bus Museum) alongside photographs and artefacts resembling battered leather-based suitcases and a Greyhound ticket poster.

Edwards gutting the bus’s inside—it had been become a house on wheels within the Nineteen Seventies Photograph: Leo Michael Nash

Felecia Gaston, the Marin Metropolis society’s founder, has recorded Black residents’ reminiscences of taking one-way journeys out of the South within the Nineteen Forties. They packed shoeboxes for the street with sturdy foodstuffs, like hard-boiled eggs, fried hen, pound cake, peanuts and raisins. “They usually at all times introduced sufficient meals to share with different folks,” Gaston says. “There have been at all times folks taking good care of one another, looking for one another.”

In Cleveland, Greyhound and Playhouse Sq. staff “are positively looking for the bus” when Edwards will not be onsite, he says. Edwards is scouting for classic seats and different automobile components aided by the Bus Boys Assortment, a staff of sellers and restorers in Minnesota. Within the virtual-reality experiences that he’s creating for bus guests, video and audio will signify Jim Crow-era interactions amongst passengers and drivers.

As Edwards strips away the bus’s Nineteen Seventies accretions, he has not but tried to unroll the delicate material vacation spot signal over the motive force’s seat. It has been paused on the identical phrase because it was mouldering in Pennsylvania: “Particular”.