The Asante Ewer is without doubt one of the most intriguing objects within the British Museum. Made in England within the 1300s, it was transported to Africa, the place it was both carried by camel throughout the Sahara or taken on an early sea voyage across the west coast, ultimately ending up within the Asante kingdom. In 1896 it was looted by British troops, together with two smaller ewers (one was taken in 1900), and returned to England.

The three steel ewers (jugs) have been introduced collectively and go on show in the present day (24 October) at York Military Museum (till 21 February). The show is accompanied by different objects seized by the Prince of Wales’s Personal Regiment of West Yorkshire throughout the Anglo-Asante Wars, together with a royal chair and sword.

The ewers will then be proven, probably with a distinct set of objects, on the British Museum (5 March-7 July 2026). Accompanying the shows is an “object in focus” e-book by the curators.

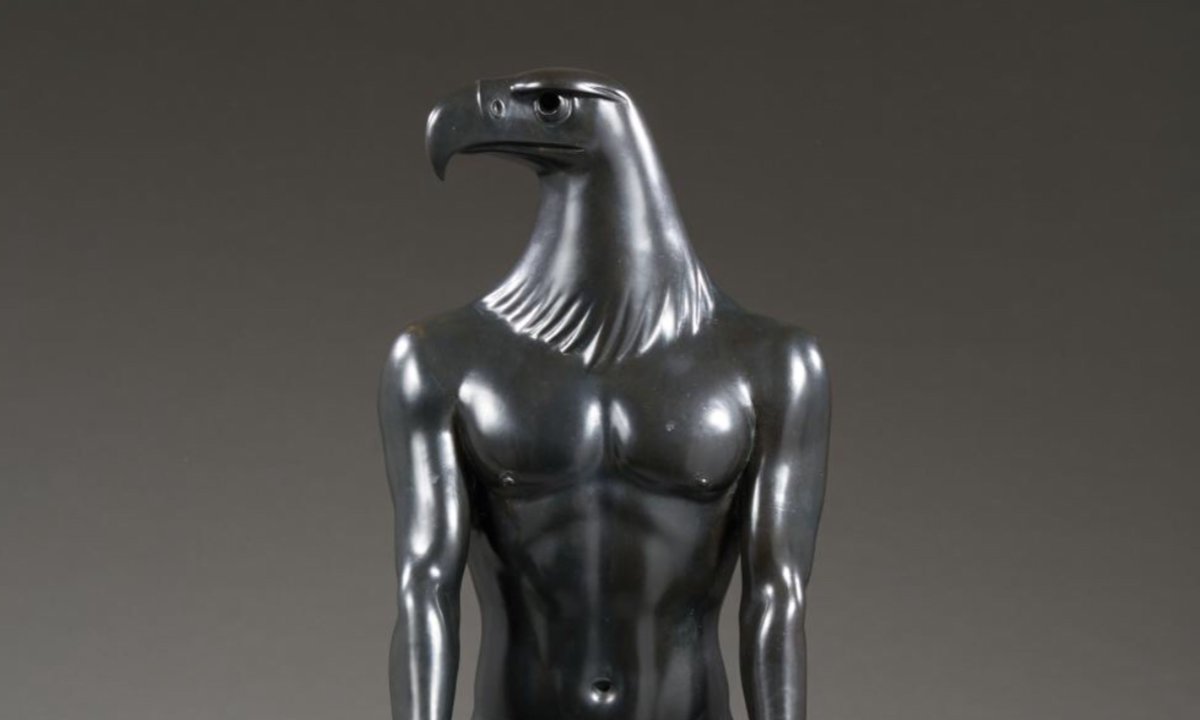

The 62cm-high Asante Ewer is the biggest surviving bronze vessel made in medieval England. Holding 19 litres, it might effectively have been made for serving wine at a grand feast, though it could most likely have required two folks to carry it.

The British Museum dates the ewer to 1340-1405. It bears the royal coat of arms and will have been made for Richard II.

How the ewer reached the Asante kingdom (in present-day Ghana) stays a thriller, regardless of the latest analysis. The 2 curators have barely totally different views, though each stress that that is hypothesis.

Lloyd de Beer believes it extra probably that the ewer was taken by sea across the West African coast, probably by a Portuguese or Dutch buying and selling ship. Julie Hudson leans in the direction of the speculation that it was carried throughout the Sahara by a camel caravan. However neither rule out the opposite possibility.

The Asante Ewer

Trustees of the British Museum

It additionally stays unknown why the ewer was despatched to the dominion or when the journey occurred, though it might effectively have been quickly after the article was made—within the 14th or Fifteenth century.

All that’s sure is that the Asante Ewer was in a royal palace in Kumasi in 1884, when it was photographed in a courtyard by Frederick Grant. It was seized by British troops in 1896, throughout intensive looting within the fourth Anglo-Asante warfare. The ewer was purchased later that yr by the British Museum for £50.

An unsure connection

Including to the thriller are two smaller Fifteenth-century ewers that had been additionally looted in Kumasi. They’re believed to have been made in England, nevertheless they may have come from the Netherlands or Germany.

One additionally ended up within the British Museum—acquired in 1933 from an officer who had served throughout the fifth Anglo-Asante Warfare. The third ewer had been acquired by one other officer throughout the 1896 warfare and was later donated to the Prince of Wales’s Personal Regiment of West Yorkshire by the governor of the Gold Coast. It’s now held at York Military Museum.

The York ewer was photographed twice at an early stage, in very totally different circumstances. It seems subsequent to the Asante Ewer in Grant’s 1884 {photograph} of the royal courtyard, the place each objects seem to have served a ceremonial perform.

The ewer then reappears in an 1896 {photograph} of Asante Warfare trophies, proven alongside weapons and several other skulls. The picture, which is described within the British Museum’s e-book The Asante Ewer as a “grotesque”, was taken by a industrial photographer in Dover, UK.

The curators conclude: “When the ewers had been faraway from the courtyard by the British army, their ritual significance was deactivated and changed with a brand new narrative—within the case of the York jug as a spoil of warfare within the regimental mess, and for the Asante Ewer as a uncommon surviving English medieval vessel displayed within the British Museum”.

It’s potential that the three ewers will likely be lent to the royal museum in Kumasi within the subsequent yr or so, earlier than going again on show on the British Museum and the York Military Museum.